And why yours might need a little therapy

By: Susan DeMatei, Founder of WineGlass Marketing

The word “brand” is notoriously difficult to define in marketing. If we were talking about a ranch brand—the kind seared onto livestock to signify ownership—that’s easy to understand. But in marketing, a brand is not a physical thing. It’s a symbolic construct. It’s not the label on the bottle or the winery’s logo or even the product itself. Rather, it’s the entire perception a consumer holds in their mind about your company, your wine, your people, and everything you collectively represent.

A brand is a conceptual identity that differentiates you from your competitors. It can be shaped by your name, your origin story, the design of your label, the personalities involved in your winery, your tasting room experience, your packaging, your email tone, your partnerships, or even how you respond to a customer complaint. All these elements come together to form the intangible yet powerful idea of your brand. It is, quite literally, everything that signals who you are and why someone should care.

The Brand Illusion & its Real-World Value

So why do marketers spend so much time discussing something that isn’t technically real? Because the effects are very real. Trust in a brand drives buying behavior. According to a 2021 report by Salsify, 90 percent of consumers said they are willing to pay more for a product from a brand they trust. And in a study by Deloitte Digital and Twilio, 68 percent of surveyed consumers reported they had spent more with a trusted brand—on average, 25 percent more.

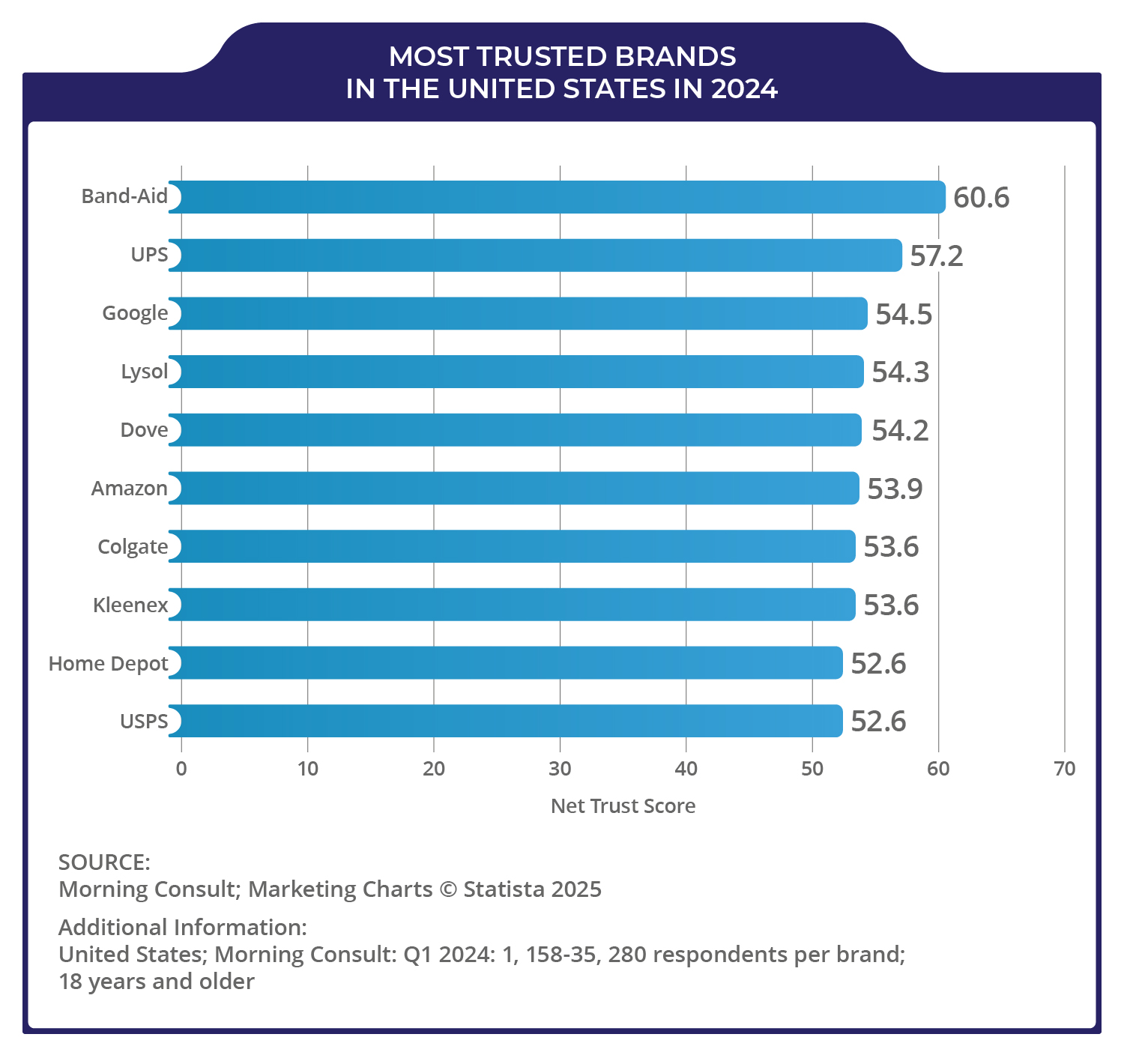

This isn’t just theoretical. Every year, major consulting firms and publications like Forbes and Newsweek publish lists of the most trusted brands. These aren’t obscure B2B companies or trendy startups. They’re names like Coca-Cola, Kleenex, and Whirlpool—brands that have become synonymous with quality, consistency, and confidence. In categories like health, beauty, and especially food and beverage, trust is essential.

Food and beverage, in fact, ranks as the most trusted industry in the U.S. According to Morning Consult’s 2022 study, 72 percent of adults expressed some level of trust in the sector. That number climbs to 84 percent among Baby Boomers and 82 percent among high-income consumers. For comparison, trust among Millennials is 67 percent, and among Gen Z, it’s just 62 percent. These generational and socioeconomic differences remind us that brand trust is not universal—it must be nurtured and earned within each target group.

The idea that a collection of products, messaging, and people can form something consumers trust enough to put into their bodies is no small feat. In wine, where the product is sensory and the market is crowded, that trust can decide between a sale and a pass.

Make no mistake—this intangible identity has tangible value. Consider when Joe Wagner sold the Meiomi brand to Constellation Brands in 2015. Nothing tangible transpired: no winery, vineyards, or staff. What Constellation bought for $315 million was a name, a label, and a loyal following. They bought the brand. The value placed on these intangible assets of a brand is referred to as Brand Equity. That’s the power of branding.

People Buy Brands, Not Products

Your brand includes your product, but it is not your product. This crucial distinction often gets blurred, especially in industries like wine, where so much attention is given to what’s in the bottle. The reality is that consumers rarely buy based on technical attributes alone. They buy based on what they feel the product represents. They buy based on brand.

Consider Halls. Technically, it’s a British brand of mentholated cough drops, now owned by Mondelēz International. That’s the company. But that’s not why people grab a pack of Halls at the drugstore when they’re sick. And if we were to describe the product the way we often do in wine—focusing on precise formulation—we’d say something like: “This is a 5.8 milligram lozenge with lemon flavoring, containing 16.1 mg of menthol and 8.1 mg of eucalyptus globulus leaf essential oil.”

Informative? Maybe.

Persuasive? Not even close.

Halls doesn’t sell ingredients. It sells empowerment. The brand message is clear: we know you’re indispensable to your family, workplace, and life. A cold shouldn’t stop you, and Halls won’t let it. It promises to clear your symptoms so you can keep going. That’s the brand. And it’s working—Nielsen reports Halls’ sales grew more than 32% in 2023, a surge not driven by a change in formula, but by a clear and resonant brand promise.

This is the essence of brand power. People don’t buy what a product is. They buy what it means. They buy it because of how it makes them feel, how it fits their life, and what it says about them. Brands create shorthand for decision-making, simplify the overwhelming, and reinforce identity. That’s true in cough drops, and it’s absolutely true in wine.

So… How Do You Protect (and Strengthen) Your Brand Right Now?

Here are a few no-nonsense steps you can take this week to make sure your brand’s identity doesn’t slip into witness protection:

1. Google Yourself (and Don’t Flinch):

What comes up first? Your website? Yelp? A two-year-old event listing? Your digital first impression is your storefront — make sure it says what you want it to.

2. Audit Your Touchpoints:

Look at your website, social feeds, emails, tasting notes, signage, even your Wi-Fi password. Do they all sound like the same personality? If not, your brand’s having an identity crisis.

3. Define What You Aren’t:

Everyone wants to be “premium,” “authentic,” and “approachable.” Snooze. Get real about what makes you different — and what doesn’t fit your vibe. That’s where clarity (and memorability) live.

4. Protect the Visuals:

Your logo, colors, and photography are your visual handshake. Don’t let them be distorted, stretched, pixelated, or used on a mauve background because someone “thought it looked nice.” Create a style guide and guard it like a secret recipe.

5. Train Your Team to Be Brand Ambassadors:

Every person pouring, posting, or answering an email is your brand. Make sure they know how to represent it — and reward them when they do it well.

6. Listen. Constantly:

Brands aren’t built in boardrooms; they’re built in the wild. Track reviews, social comments, and customer emails. They’ll tell you what your brand actually means out there — not just what you hope it does.

The Bottom Line

Your brand is the most valuable asset you own — even if it never shows up on a balance sheet. It’s perception, emotion, and memory all wrapped into one name. It’s what turns a tasting into loyalty, a label into a lifestyle, and a sale into advocacy.

So don’t just make great wine. Make a great impression — again, and again, and again.

Susan DeMatei founded WineGlass Marketing, the largest full-service, award-winning marketing firm focused on the wine industry. She is a certified Sommelier and Specialist in Wine, with degrees in Viticulture and Communications, an instructor at Napa Valley Community College, and is currently collaborating on two textbooks. Now in its 13th year, her agency offers domestic and international wineries assistance with all areas of strategy and execution. WineGlass Marketing is located in Napa, California, and can be reached at 707-927-3334 or wineglassmarketing.com