By: Trevor Troyer, Vice-President of Operations for Agricultural Risk Management

What is Federally subsidized crop insurance? What is Grape Crop Insurance and how does it work?

The Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) was created in 1938. Originally coverage was limited to major crops. It was basically an experiment at that time, until the passage of the Federal Crop Insurance Act in 1980. The 1980 Act expanded the number of crops insured and areas in the US. In 1996 the USDA Risk Management Agency (RMA) was created. RMA’s purpose was to administer the Federal Crop insurance programs and other risk management related programs.

Perennials are very different from traditional row crops or vegetable crops. But a lot of the risks are very much the same. Drought, freeze, wildlife damage, fire/smoke and the list goes on. From what can be seen the risks can actually be more with perennials. It doesn’t matter if it’s an apple orchard, avocado grove or vineyard, your investment is subject to the elements all year round. Things may happen after you harvest that might affect the following year’s crop production.

Grape Crop Insurance goes back to 1998, the current policy was written in 2010. Crop insurance is a partnership with authorized Insurance companies and the FCIC. Crop insurance is partially subsidized through the USDA. Currently there are 13 Approved Insurance Providers (AIPs) authorized to administer crop insurance policies with the USDA. Prices and premiums are set by the USDA per crop, state and county. There is no price/premium competition from one company to the next because of this. Independent insurance agents sell for these 13 different insurance providers.

Grape crop insurance is available in the following states; Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Idaho, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Virginia and Washington. Crop insurance is not available for grapes in all counties though. Insurable varieties are also different between states and counties. As mentioned, before prices are different between states and counties as well. The USDA price for a ton of Pinot Noir in Oregon is different than a ton of Pinot Noir in New York.

Grapes are insured under an Actual Production History (APH) plan of insurance. An average of the vineyard’s production per variety is used. Grapes need to be in their 4th growing season to be insurable. A minimum of 4 years is needed to do the average, if the grapes have just become insurable then a Transitional Yield (based on the county and variety) is used in place of any missing years. A maximum of 10 years can be used to determine the average if a vineyard has been in production for that amount time. Basically, you are insuring an average of your tons per acre per variety.

With crop insurance you cannot cover 100% of your average production. You can choose coverage levels from 50% to 85%. There is a built-in production deductible. Coverage levels are in 5% increments. Coverage levels are relative to premium, the lower the coverage the lower the premium, the more coverage you buy the higher the premium. It comes back to how much risk you feel safe with. For example, if you have Cabernet Sauvignon and your average is 5 tons per acre. At the 75% coverage level you would be covered for 3.75 tons per acre. You would have a 25% deductible (1.25 tons per acre). To have a payable loss you would have to lose more than 25% of your average production in a year.

Crop insurance is designed to help a grower have enough money to be able to produce a crop the following year. It is not set up to replace profits lost from an insurable cause. I have had winery owners complain to me that it doesn’t cover the cost of how much their wine is worth. While I can totally understand this, it is the growing costs that are being insured against loss. Crop insurance does not cover the production costs of making wine or juice etc. Only the Causes of Loss that are listed in the policy are being insured against. It doesn’t cover the inability of a grower to sell his grapes or broken contracts with wineries or processors.

Here are the Causes of Loss for Grapes from the National Fact Sheet from the USDA:

Causes of Loss

You are protected against the following:

• Adverse weather conditions, including natural perils such as hail, frost, freeze, wind, drought, and excess precipitation;

• Earthquake;

• Failure of the irrigation water supply, if caused by an insured peril during the insurance period;

• Fire;

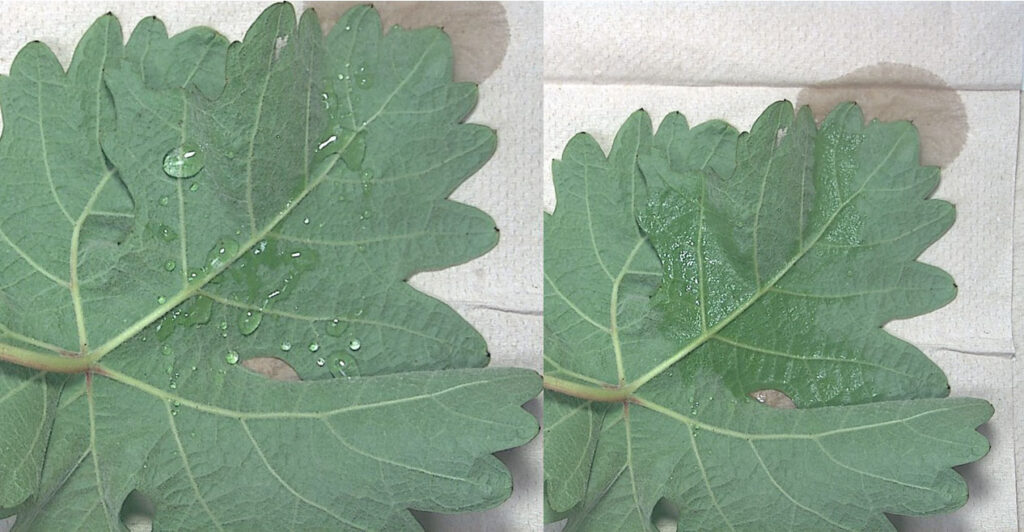

• Insects and plant disease, except for insufficient or improper application of pest or disease control measures;

• Wildlife; or

• Volcanic eruption.

Additionally, we will not insure against:

• Phylloxera, regardless of cause; or

• Inability to market the grapes for any reason other than actual physical damage for an insurable cause of loss

Crop insurance is partially subsidized through the USDA. Premiums are subsidized from 100% at Catastrophic Coverage (there is an administrative fee though) to 38% depending on coverage level chosen. A lot of growers “buy-up” coverage from 65% to 80% and their premium subsidy is around 50% to 60%.

Hopefully you don’t have a lot situations where you would have a loss. But as a grower you need

to assess your risks. These have to be taken into consideration for the growing region your vineyard is located in. Here are some other questions to ask yourself. What are your break-even costs? Do you know your cost of production with projected inflation? Have you evaluated the risk of a severe crop loss? What varieties are planted in your vineyard? Some types of Vitis vinifera are more susceptible to weather issues than others. Are you able to repay current operating loans without crop insurance in the event of a loss?

Our job as a crop insurance agent or crop insurance agency is not to convince you that you need crop insurance. It is to help you make an educated decision, based on your risks, on whether or not you need crop insurance. And then, if it is a good fit to mitigate your risks, to determine how much coverage is needed. No one wants to have a loss but they do unfortunately happen.