Page 57 - Grapevine JanFeb 2022

P. 57

Around The Vineyard

this, and we already know how to control them.

The difference may be that SWD are attracted not

only to overripe berries but to ripening berries as

well, stretching out our timeline for management.

The Big Fuss About

Spotted Wing Drosophila

SWD is not native to the United States or Canada,

but it is now prevalent throughout fruit-growing

regions of North America. It was accidentally intro-

duced from east Asia in 2008, likely via cargo as

with many invasive pests. It quickly spread through-

out the continent, costing the US strawberry, blue-

berry, cherry, and raspberry industries millions of

dollars; in Minnesota raspberries alone, the pest

causes over $2M per year. The costs come in the

form of damaged fruit, lost marketable yield, and

frequent, expensive insecticide applications.

The feature that makes SWD special from other

fruit flies is that the females have a serrated “ovi-

positor” that they use to pierce the soft skin of

ripe berries to lay eggs inside the fruit. Those eggs

become larvae (maggots) that feed on the fruit,

making it mushy and unsalable. Both male and

female SWD can also introduce bacteria to the

berries that cause fruit rots. They begin to become

attracted to fruit when it is ripe or nearly-ripe fruit

and do not infest green, unripe berries.

Learning what problems SWD poses for the grape

industry will help growers decide if spraying for

SWD is a worthwhile expense.

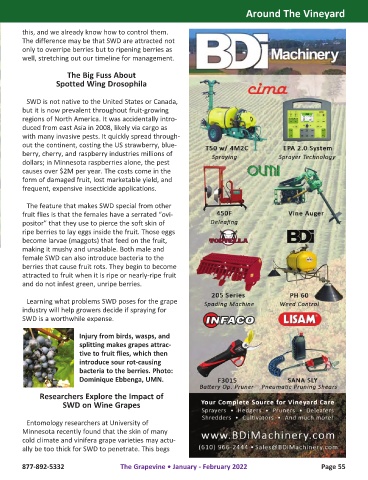

Injury from birds, wasps, and

splitting makes grapes attrac-

tive to fruit flies, which then

introduce sour rot-causing

bacteria to the berries. Photo:

Dominique Ebbenga, UMN.

Researchers Explore the Impact of

SWD on Wine Grapes

Entomology researchers at University of

Minnesota recently found that the skin of many

cold climate and vinifera grape varieties may actu-

ally be too thick for SWD to penetrate. This begs

877-892-5332 The Grapevine • January - February 2022 Page 55

Grapevine Main Pages GV111221_Layout 1-1 copy.indd 55 12/16/21 3:29 PM